|

One of the often stated goals of physical education is to promote engagement in physical activity outside of the school gate. However, when I ask my own students what opportunities exist for them to be active in their communities, they are quick to point out the spaces where the activities are pre-defined (i.e. basketball, tennis court, golf course etc.) and while they are also able to identify trails and parks nearby, they had a harder time thinking more abstract about the movement possibilities that could be found in these open, undefined spaces. As we sought to address this, the challenge was that our school is a rural campus, which draws students from all over the surrounding area - some students live in rural farm communities while others live in the suburbs or city. To explore how students could be active in their community, would mean identifying activities that were transferable to many communities. The activities we chose for the unit were trail biking, soccer, softball. While soccer and softball can often use specialized facilities, they are also games that can be organized in open spaces with minimal equipment, with substitutes for bases or markers for goals. The towns and cities our school draws from, have strong trail and pathway systems which students could access via bikes. For one class, park games (target/law games, and slackline) were chosen instead of soccer. Lesson Progression For 3-4 lessons, student sampled each activity. The biking progression we used started on pavement and flat trails before moving to more difficult trails, and finally student-directed biking challenges. At the end each 'activity sample' students reflected on the features of each activity that resonated with them most. As 'fun' seemed to be the dominating feature, we spent some more time unpacking exactly what about each activity was fun (through which the other features became more prevalent). In interviews, students mentioned how the sense of freedom and adventure were what made biking fun, while previous positive experiences, confidence and social dynamics were motivators for fun experiences in softball and soccer. After the periods of sampling were complete, it came time for student's to make choices of which activity they chose to engage in. The below photo shows the choice board. At the beginning of class, students would move their magnet to indicate their choice but also consider why they were making that choice. Logistically, on some days we would only offer 2 of 3 choices so we could manage supervision. This process continued for an additional 3-4 lessons. Heading Out into the Community We ended the unit by actually heading out into a nearby local community where these activities could take place (and nearby where some of our students live). The local park recently built a pump track (left), which seemed to be the popular choice for many, while others preferred to head out on the pathways or find some dirt jumps. Of course, there were a number of students who were quick to organize softball and soccer games as well. Student Interviews As part of an on-going project to better understand how implementing the meaningful PE framework is impacting our students, we interview a group of 15-20 students at various points throughout the year. At the end of this unit, one pointed question we asked was "through this unit, explain how your understanding of how to be active in your community improved, or stayed the same?". About 60% of the students noted their understanding of how to be active in the community improved, noteable responses include:

Quantitatively, we have been surveying this entire grade anonymously for the past 2 years using questions related to the features of MPE, and a likert scale. After stagnation in questions related to 'seeing the connections between PE and life outside of school' we have seen a notable uptick in students 'agreeing' or 'strongly agreeing' that they now see these connections. While I think this unit certainly speaks to the importance of democratic and reflective practice when applying the meaningful PE framework, I believe it also speaks to the importance of being intentional with our learning design. A "Field Games" unit, might very well imply opportunities to engage in these activities in the community. However, if the one of the goals of PE is to inspire participation outside of school, then this shouldn't be something left to chance.

0 Comments

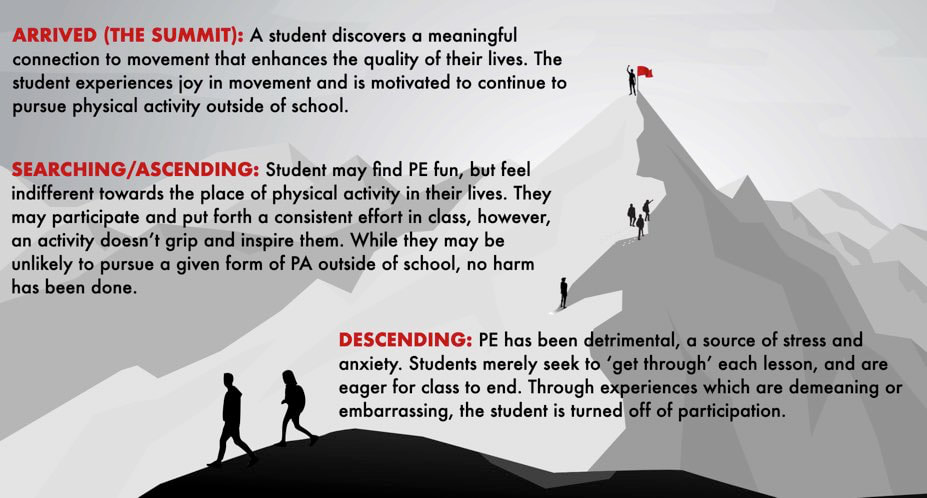

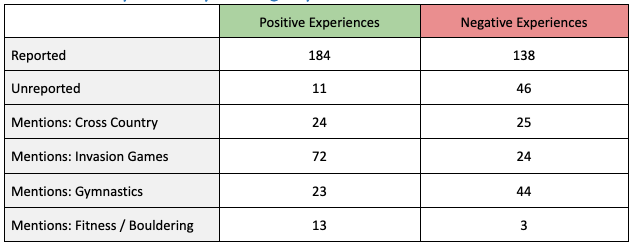

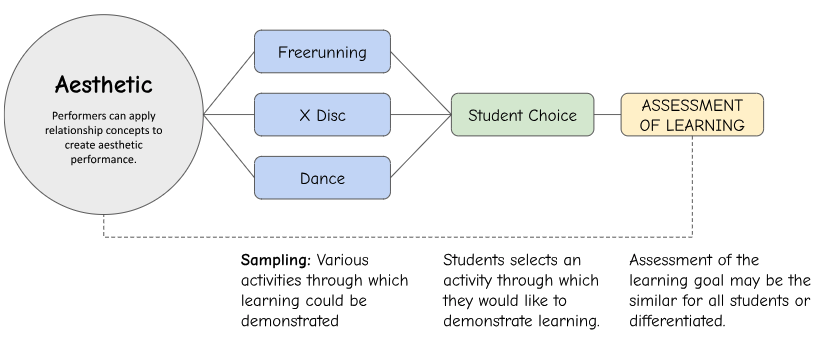

There is no doubt that Physical Education has many aims and employs a variety of different practices in order to achieve those aims. Regardless of the the approach, I believe PE still has 3 broad outcomes (pictured below) of which the greatest outcome is a participant becoming motivated to pursue physical activity in their own lives across the lifespan. I think that many teachers probably believe in some iteration of this, but often teachers (myself included) can also forget that the opposite can also occur. We want to believe that PE is good for all students and lean on the health benefits or more recently the enhancement of academic performance to advocate for its importance. While there is certainly merit to those arguments, we often conveniently ignore PE's potential to cause harm. Earlier in my career, I've been guilty of stating "they will eventually find an activity they enjoy" (as part of a multi-activity approach) or nodded in agreement when someone states that PE is just "not student X's thing". If you would like read more about do no harm mindests check out Alex Beckey's (@ImSporticus) blog here To understand more about how students experience our PE classes, last year, we collected survey data from our MS students that asked them questions related to their experiences in PE the past semester. Many of the questions were connected specifically to the features of the meaningful physical education (MPE) framework. You can read more about how this data provided evidence for a meaningful PE approach here. Two of the questions asked students to describe a positive and negative experience in PE during the past semester, with a final question asking students to generally summarize their PE experience as being generally; very positive, somewhat positive, neutral, somewhat negative or very negative. As you can see above, the sources of the negative experiences (based on the frequency of mention) amongst our Junior High / Middle school students seemed to arise primarily from Cross Country running and Gymnastics units. Our revised approach to a Trail Running / Challenge unit (né Cross Country) can be found here. It has since come time for us to revisit our Gymnastics unit to see if we can facilitate a more positive student experience. In the survey, students indicated that a lack of relevance and having to display their performance in front of others were the most common reasons for a negative experience. It is important to note that our curriculum (MYP) requires students to complete a movement composition piece each year, so avoidance is not an option! We begun by asking the question of "why", why do we want students to participate in gymnastics? Not surprisingly, it was not because of our own aspirations to have an Olympic gymnast represent our school. Rather, gymnastics is seen as an opportunity to demonstrate creativity and improve our general movement capabilities. If that is the 'why', then certainly there are more activities that meet that criteria that just gymnastics. With that in mind, we wanted to focus on three different activities, to explore how performers can apply relationship concepts (matching/contrasting, with obstacles, with implements) to create an aesthetic performance. The purpose of exploring a concept, is that it lends itself to multiple forms of expression. Students would sample each activity before making a choice of which they would use to create an aesthetic performance.

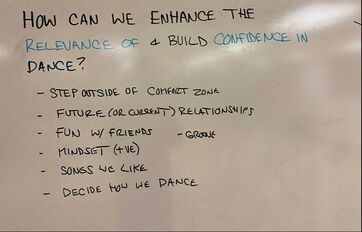

During that period of sampling, I was particularly interested in students perceptions related to dance. In our Semester 2 data collection, students also had fairly negative perceptions towards dance (as I write that sentence, it occurs to me that combining students two least favourite units into one might not result in the desired outcome....). After an introductory lesson on dancing, each student was given an equalizer reflection (credit: @ImSporticus). After explaining how the equalizer works, I asked students to fill it out for their favourite activity, rating it on each feature of MPE. After that, I asked students to repear that process and fill it out for dance in a different colour. If the favourite activity and dance were the same (I had a hunch it would not be), then they would just make a note. Some examples below: Not surprisingly, no students indicated that dance was there favourite activty to do, with the exceptions of one student who preferred a different style of dance. As a follow up question, students compared the two activities and were asked "Which feature has the biggest gap between your favourite activity and dance?" Interestingly

The strategies that the class came up with were very different. Class A ended up deciding that they wanted to build confidence and continue to practice 'Cadillac Ranch', but were going to approach it with a different mindset and focus on connecting with friends rather than worrying about how they might look. Class B tried to enhance fun by creating dances that represented their favourite activity. Some students performed dances with hockey sticks, where they incorporated 'the Michigan', while others focused on creating a line dance to a Taylor Swift song. Culminating Activity After exploring additional activities (free-running & x-disc), students made a selection of which one they would like to emphasize in creating an aesthetic routine in which application of relationship concepts, complexity and flow were the common criteria. Below are a couple videos of students practicing some of the activities. Rather than insisting on a live student performance, students had the option to perform or submit a video. As we had several options, with students rehearsing different skills, students never seemed to notice whether anyone was watching or not.

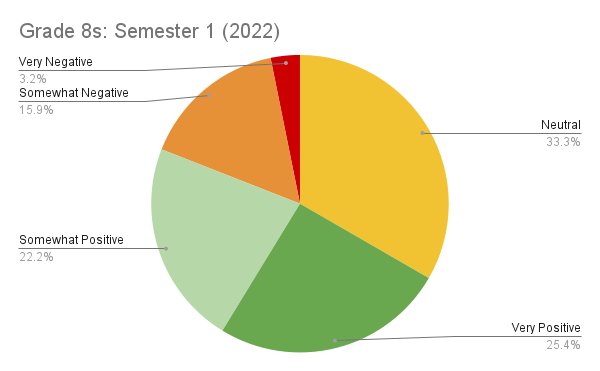

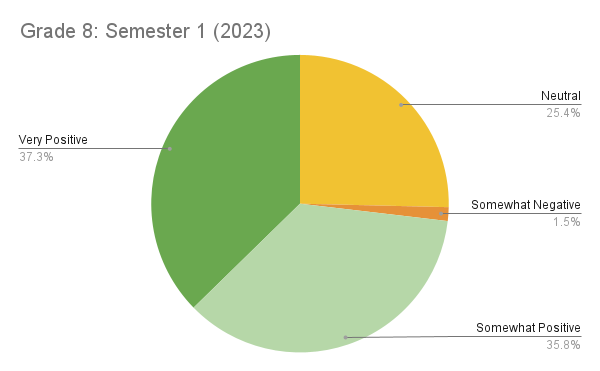

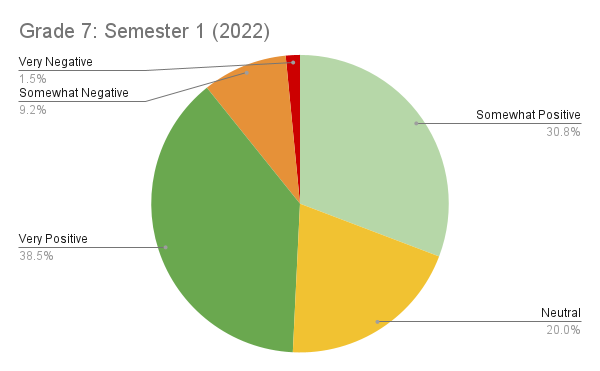

2023 Questionnaire At the conclusion of the unit, we repeated the same questionnaire we repeated the previous year. While all the data will be analyzed at another point in time, the first question I looked at was students general perceptions of PE this semester (with a revised approach to both Cross Country Running and Gymnastics). In the graphs below we see a significant reduction in the reporting of negative PE experiences of last years Grade 8 students from semester 1, 2022 (left) to the current years Grade 8 students in semester 1, 2023 (right). Whereas the graph above shows the differences between students in the same grade level in two different school years - the graph below shows the self-reported experiences of the same group students, when they were in Grade 7 the previous year ('same', is used loosely as there is changing enrolment). In Grade 7 students, also would have participated in running and gymnastics units. Again, with a greater emphasis on the MPE framwork, we observe a noticeable decline in the reporting of negative experiences Concluding Thoughts The goal of the MPE framework is to empower students to take responsibility for engaging in physical activity outside of the school gates. With that in mind, has this revised approach to a movement composition achieved that aim? Well, I did not receive any Christmas cards from the local parkour, gymnastics or dance studios - so perhaps not! In terms of the data, the amount of students reporting an at least somewhat positive PE experience has remained consistent when comparing Grade 7 to Grade 8 data of the 'same' group of students. However, as Alex Beckey cites in his blog post (linked in the opening paragraph), a negative experience may be more powerful than a good one (Baumeister et al, 2001). While this approach (alongside others applied this semester) may not have led student to the 'peak' of physical education, at the very least, it has perhaps prevented students from a detrimental experience that may otherwise dissuade them from participation. 'Raising the floor' of our physical education program, where a neutral (and perhaps one day, a 'somewhat positive') is the bare minimum of student experiences, seems like a worthwhile endeavour, and the MPE framework has certainly been useful in that regard. References Baumeister, R. F., Bratslavsky, E., Finkenauer, C., & Vohs, K. D. (2001). Bad is Stronger than Good. Review of General Psychology, 5(4), 323-370. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.5.4.323 At the Meaningful PE Symposium this past May, Dr. Justen O’Connor outlined a compelling contrast between formal and informal sport during one of the most thought provoking presentations in recent memory. In formal sport, decisions are largely made by governing bodies, who (using cross country running as an example) decide on how students should be grouped (by age and gender) and which distance they should run. Whereas in informal sport, decisions are largely made by participants who might decide which route they run, when they want to run, or consider which route will allow group participation. This is an oversimplification of Dr. O’Connor’s presentation, but wished to give credit where it is certainly due. The purpose of this blog is to summarise how our MS department has attempted to apply these ideas through the lens of MPE.

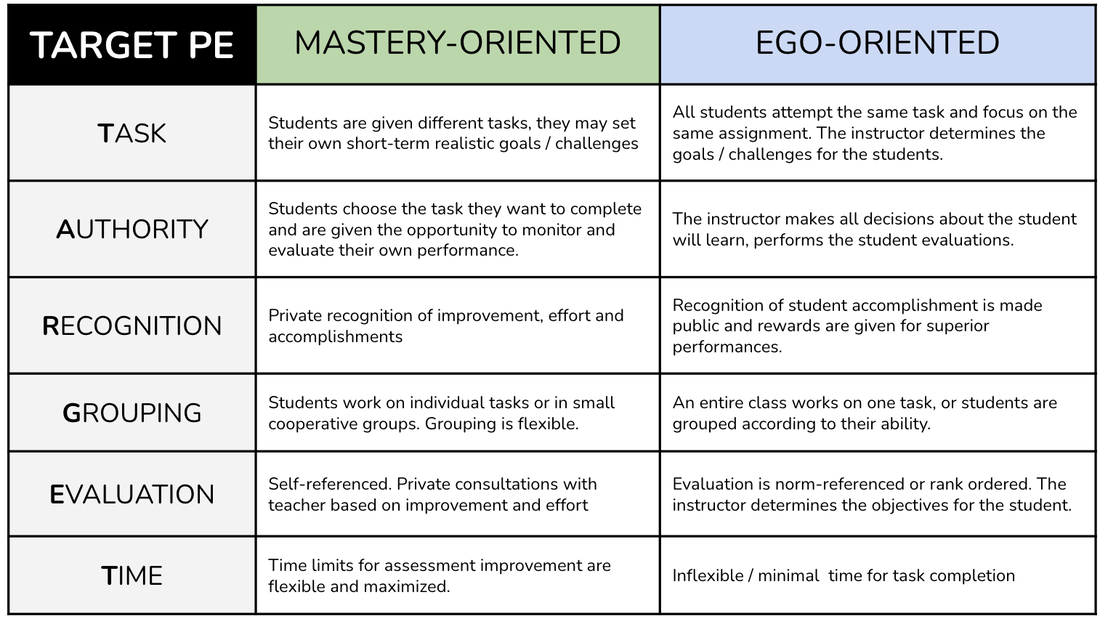

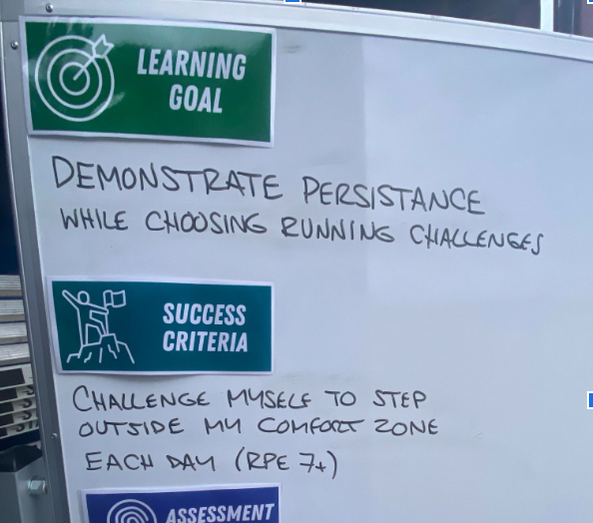

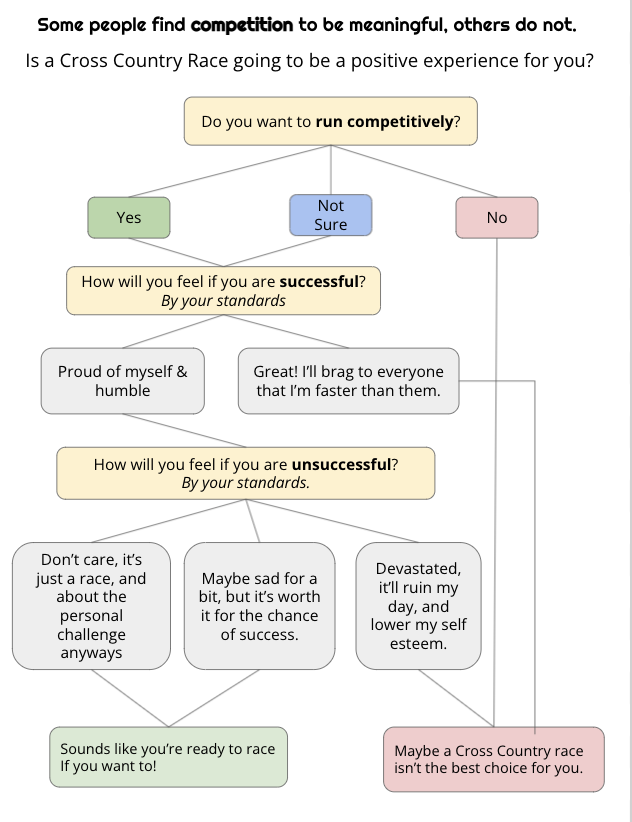

Our school has a rich tradition of formal running (i.e. Cross Country) and boasts a number of provincial championships. Traditionally, the Middle School (Grade 7-9) PE program has aimed to connect kids with these formal sport opportunities. In PE classes, students previously trained for an in-school meet where they would run the distance that was assigned to their age/gender by our governing body. The top students from that meet are invited to divisionals, to zones and so on. While formal sport is certainly meaningful to some students, over the past few years we’ve recognized that this is not necessarily inclusive or engaging of all students. Should a PE program be devoted to leading students towards formal sport participation that is unable to include all of them? In our Elementary School, attempts to reconcile this dilemna has led to the creation of a Who We Are Outdoors unit, as an attempt to help students find more meaning in the outdoors by exploring other activities besides running. We have been reluctant to take a similar approach with the Middle School, because we still see running as an activity that students can participate in across their lifespan. But, how can we do that in a way that is more meaningful to all students? Fortunately, one of many beautiful things about the MPE framework, is there is not only one way to apply it. We began by using the TARGET PE model as a way to reflect upon our previous approach to this unit. Not surprisingly, as we were heavily aligned with a formal sport offering, much of the unit design was ego-oriented. Task and authority were controlled tightly by the teacher (as influenced by the governing body), students had very little autonomy in the challenges they wished to pursue. Recognition was given to students based on rank, classes were grouped based on their formal sport designations (gender / age) and the timing of the unit was built around the formal sport calendar (i.e. ensuring our in school- -meet was done in time to get kids qualified for the divisional meet). Moving ForwardLooking to move forward, one of the first things we discussed as a group is “why”, why do we believe students should run? Not surprisingly, the answer really wasn’t about supporting formal sport or winning trophies - it was because we wanted students to challenge themselves. With that in mind, we wanted to be intentional about the unit, and specifically renamed it so - "challenge". In our initial lessons, we presented our learning goal (below). Students began by running a short route, and self-assessing themselves based on a rate of perceived exertion. We discussed with students ‘how they knew’, and encouraged them to listen to their bodies. From there, we co-created the success criteria with students, by asking them at which point they felt they began to step outside their comfort zone. They identified that at about a ‘7’, they started to get a bit uncomfortable so that’s what we went with.

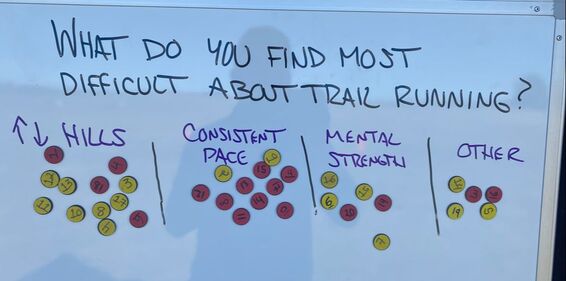

At different intervals, we would ask students to identify what it is they were struggling with most in relation to trail running (below). As we had two classes and two teacher's at the same time, we offered different ‘workshops’ to support students' needs. For the main event, we transformed our traditional formal school meet, to appear more similar to a community running event. Students chose the distances they wished to run, and students were no longer grouped by grade or gender. We added in a relay option, where students would run 2km and then tag off with a friend. Rather than mass-starting runners where it becomes very evident who is last, we decided to wave or corral start. We removed placing / ranking as being a qualifier for our XC team so students could focus on their approach to challenge and not stress about how they might compare to others. Prior to the event, students set goals related to their participation, some just wanted to finish, some wanted to improve on a previous year's time, some wanted to have fun, and some wanted to finish near the top. As the event drew closer, student participation became more autonomous, as students worked towards their individual goals. Rather than waiting for a teacher to give them an ‘official time’ students would arrive, pick up a wrist stopwatch (if they wanted), report to a teacher and off they went on the route of their choice. WAS THIS APPROACH SUCCESSFUL? We considered this unit as an 'experimental' unit, and thus wanted to correlate the data from numerous sources to determine it's success. In addition to student performance and reflections discussed below, qualitative survey data and focus group data, has not yet been collected at this time but will be in the coming weeks. Student Performance: One area of concern within the department related to what impact would offering students choice have on their performance? In theory, they might very well enjoy the unit more than previous years, but if students just opt for the easiest challenge and don't actually demonstrate persistence themselves, is that defeating the purpose? So, after the event, I crunched the numbers from the 4 previous years of races, and looked at performance across similar grade levels as well as performance of the individual sudents across multiple (I will term the 3 previous years as formal sport years, and the version above as the MPE year).

Student Reflections: At the end of the unit, students completed a private reflection. I provided some sentence stems that I 'borrowed' from one of Mel Hamada's blogs (thanks, Mel!).

Some responses from my one of my classes below: I have changed my thinking about running because last year I just ran because I had to but now I actually enjoy running I was able to cut my time down by 5 minutes. Even though it may not seem like a major difference but to me that is a lot because in grade 7 I’m pretty sure my first ever time was 25-27 minutes and I’m very proud that I was able to start being quicker. I have changed my thinking about what a successful run is because at first I kept comparing my times to others to decide whether I was proud of myself or not and now I compare my times to my own times and I am just trying to achieve a personal best. I also improved on my persistence by a lot. I got better at not stopping to walk when I got a cramp and it improved my time a lot. I am proud of myself because I never thought I was a good runner or that I could run. Now I know that if I try my best and push myself every run I can get better. I have changed my thinking about my abilities, as now I have experienced Race Day, I know what I really am capable of, and know I can be so much more. When I think about this Unit and what I have learned, I feel that if you “feel” like you are outside of you comfort zone, you can push through so much more, and achieve the unthinkable. ...but what about the formal sport?Our approach is this unit was never anti-formal sport. Formal sport has a lot of meaning for some of our students, but wasn't engaging or inclusive of every kid. Our aim was to connect students with challenge, allow them to make some choices in their participation, celebrate the success of each individual and hope to foster a connection to running that students can take with them in the future. A purpose which we see as serving the needs of every student, regardless of whether they intend to compete in formal sport or not. But wouldn't you know it, with this new approach and removal of the ranking system for qualification - the # of students interested in our formal sport team has never been higher! After the conclusion of our school event, we had over 110 students (more than 50% of our MS population) who chose to compete in the divisional meet, the largest runner population of any school (despite being half their size). This past week, that group went on to compete in the Zone championship and won it (as high as it gets for us in Middle school).

While there is still data to collect and sort through - prioritizing meaningfulness and shifting away from feeding formal sport in our PE classes, has neither jeopardized performance or formal sport in anyway, while also importantly better serving all our students. Sometimes, you can have your cake and eat it too (I think). After a lengthy process, our school is moving forward with a new timetable structure for the following year. The timetable impacts our PE programming in a number of way, summarized in the table below, for reference. The adjustment from a full year to a semester program, alongside an overall increase in teaching minutes for each course has provided a number of new challenges, but also an opportunity to re-design the curriculum to best need the needs of our students. Step 1 - Key Considerations To this end, I leaned on the appropriately named article Selecting Content to Teach in High School Physical Education (Gillispie et al, 2023). The authors outline 4 key considerations to consider when selecting course content.

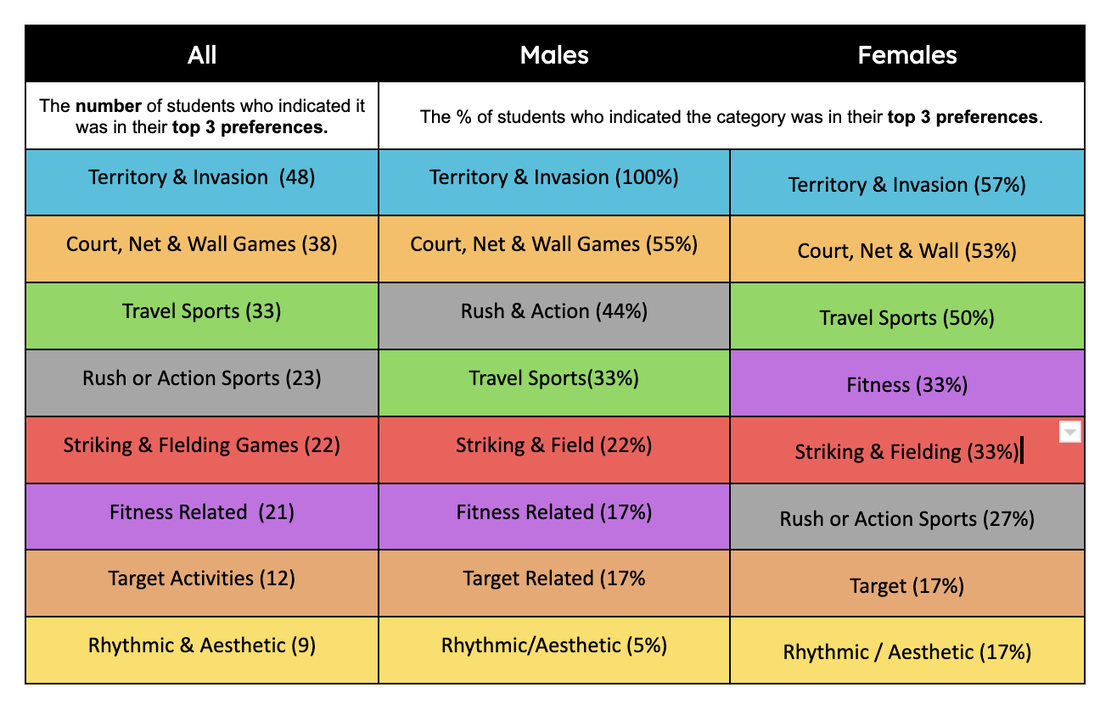

If we want to design a PE program that engages students and inspires them to be active in their local communities, an analysis of both of those considerations would be a worthy endeavour. We designed a survey based on the re-classification of activities recently put forth by O’Connor, Alfrey & Penney (2022) on re-thinking the classification of games and sports.

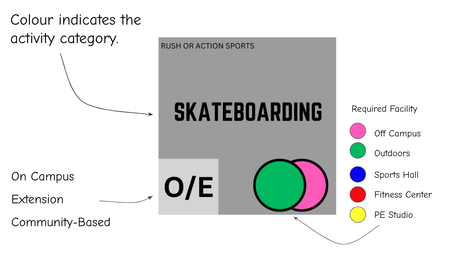

Within each category we compiled a list of all the activities available in the community that would fall within each category, as well as ones that were prevalent in our geographical context (consideration 1 & 2). We decided to include activities that we have no idea whether it was feasible for us to offer - rather than not including it, we figured if students showed interest in it, it might be worthwhile to figure out if logistically we could make it work. We administered the survey to students based on their grade for the upcoming school year (e.g. we surveyed Grade 9 students, who will be next years Grade 10s). Within each category students selected the top # from that category they were interested in. Students also indicated which category they generally would look forward to the most. As you can see from the table above. Our boys and girls were generally interested in the same categories of activities, albeit in different proportions. However, what was really interesting was the activities within each category that each gender wished to participate in. A curriculum with content designed for our boys would include flag football, kayaking, combatives, baseball, golf and training for sport performance. Where as a curriculum with content based on our girls interests would include; basketball, paddle-boarding, volleyball, trail-walking, skateboarding and yoga. Step 2 - Further Categorization Like most schools, we don’t have the luxury of programming everything we want when we want. There is a consideration of budget, facilities, teacher allocation and so on. To take this all into consideration, I put each activity onto a 3 x 3 magnetic card.

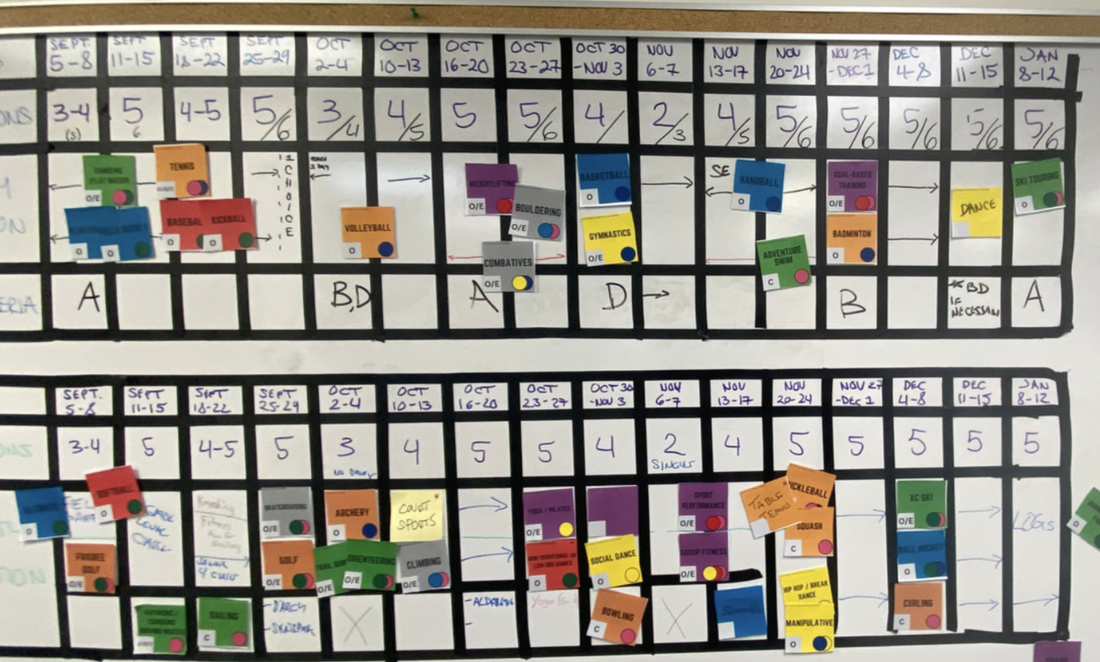

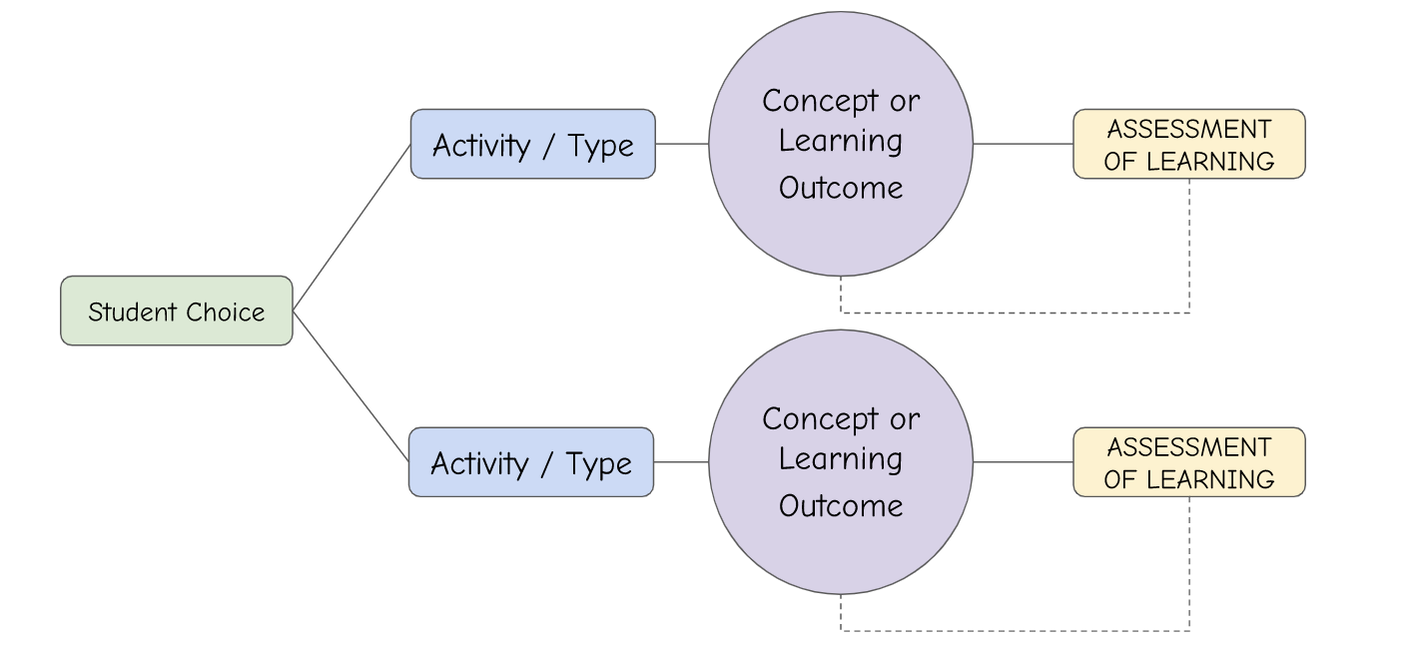

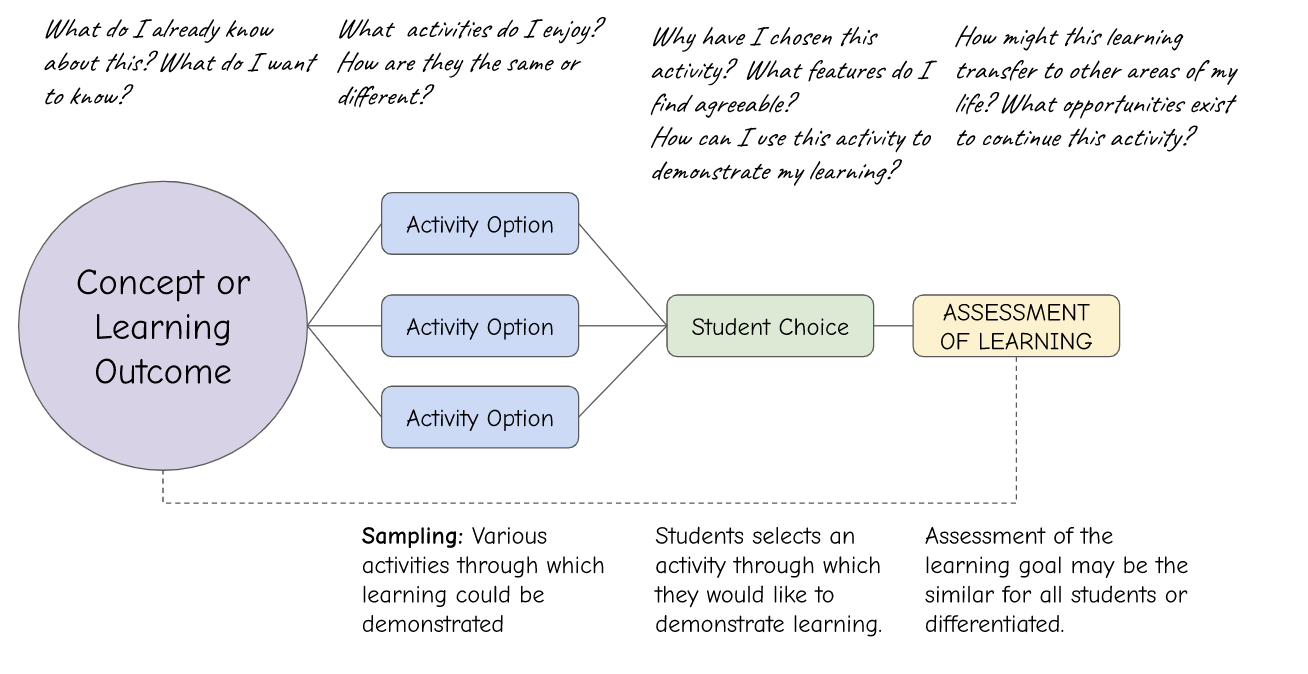

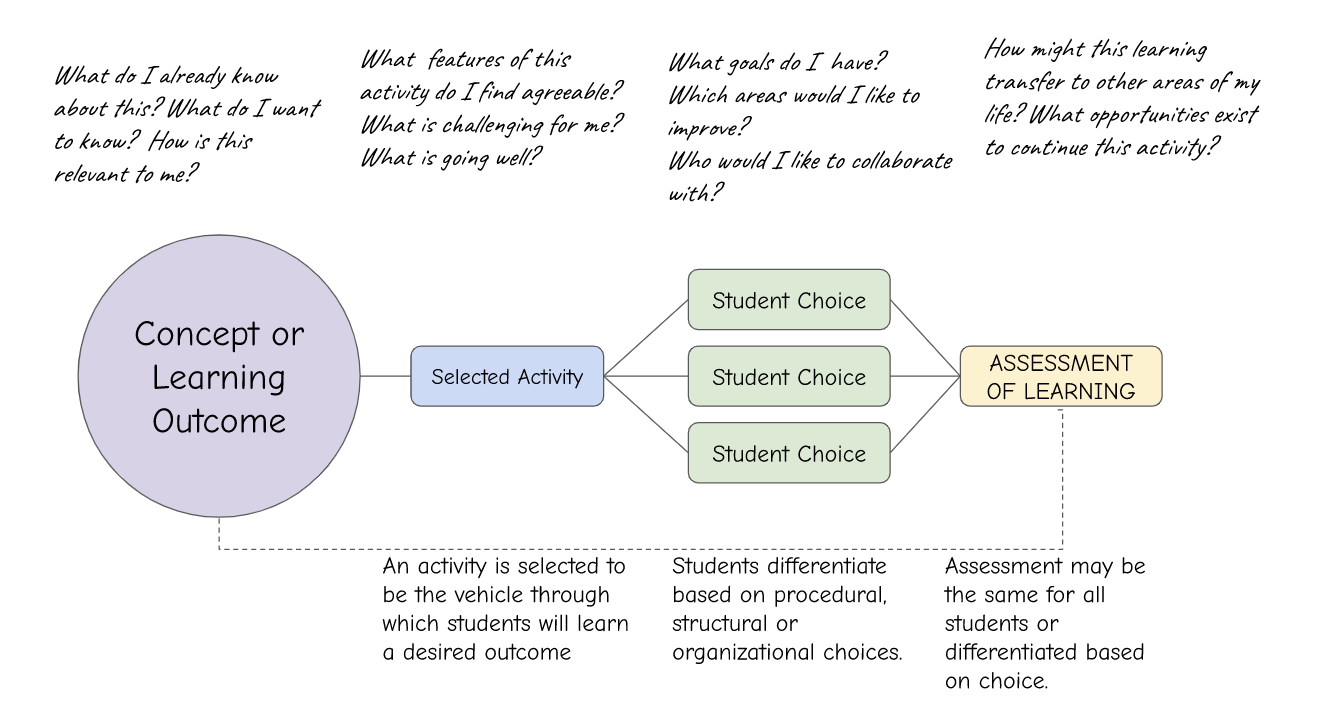

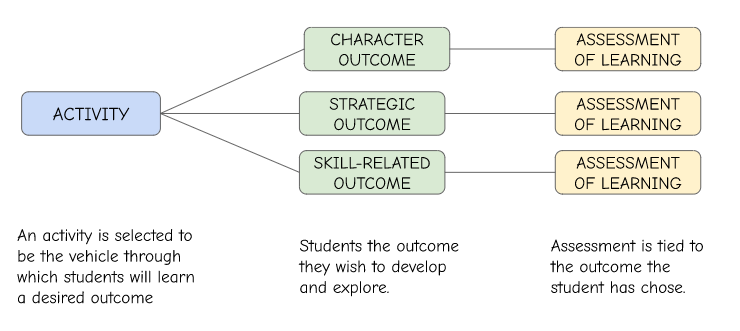

Step 3 - Mapping it Out Finally, it came time to actually hash it out in terms of which activities would fit where. On the whiteboard, we first ranked the activities based on students' interest (shown right). Generally speaking, we wanted to ensure that in each grade level there were (i) different coloured cards thus representing a variety of activity categories (ii) that the highest ranked activities were included. There were some exceptions as even though ‘dodgeball variations’ was the most popular target activity, we weren’t really willing to build a unit around that, but would incorporate it into some fun ‘options’ days. With two classes stacked in each period (i.e. two grade 10 classes at the same time) we wanted to leverage our ability to offer students choice, but during other units, keep students together (for social reasons) or rotate classes between two activities. The below image shows the messy version as we pieced together on the whiteboard. Summary: The Content of PE & Meaningfulness While we are not quite at a finished product (some fine tuning for the exact # of lessons is still required), we do feel that we've tried our best to honor designing a program that represents students interests amidst a changing contextual landscape. In my ideal world, the units would focus less on activity and more on categories or concepts that would allow multiple forms of exploration within each concept or activity category, however, the bandwidth for what would be another significant change in an already chaotic end of the school year just wasn't there. It is important to note that while the categories proposed in O'Connor et al's article, which informed how we designed our survey, will certainly allow students to participate in content (activities) that may become meaningful to them - that is only one piece of the puzzle. For example, a student may be interested in soccer, but if during our soccer unit all we teach are tactics and skills that be used to gain a competitive advantage in soccer: then how will a student who simply wants to engage in an informal game of soccer for social reasons find it to be meaningful? In the article, the authors propose a number of example questions/outcomes that extend beyond tactics needed for winning or losing. For example, what could we do to make the competition more equal or more enjoyable? In what ways can I support the team? While the content of PE can certainly set the stage for meaningful experiences, there is still a need to align the content (the what) with the pedagogy (the how). References: Justen O’Connor, Laura Alfrey & Dawn Penney (2022): Rethinking the classification of games and sports in physical education: a respect to changes in sport and participation, Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy. DOI: 10.1080/17408989.2022.2061938 Olivia J. Gillispie, Emi Tsuda, James D. Wyant & Eloise M. Elliott (2023) Selecting Content to Teach in High School Physical Education, Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 94:3, 11-16, DOI: 10.1080/07303084.2022.2156939 Facilitating meaningful experiences for students is not without challenge. While it is perhaps simple enough to understand that the features of meaningful physical education; challenge, social interaction, enjoyment, personal relevance and social interaction are influential in the way students experience PE and thus, deserving of prioritisation, it is the different ways in which students interact with those features wherein lies the challenge. Some students will prefer social settings with their friends, while others may prefer new social situations to work with new people. A challenge that is optimal some students may be too easy or too hard for others. What one student mind find interesting and fun, others find boring and irrelevant. Accounting for the diversity of student preference and experience, while rewarding, can be difficult in terms of pedagogy. Fortunately, Ní Chróinín, Fletcher and O'Sullivan (2021), outlined two key pedagogical principles that support the prioritiziation of meaningful experiences; democratic and reflective practice. Democratic practice generally refers to students having a sense of autonomy in their learning whereas reflective practice a tool for students to make sense of their experience and inform future directions. While the purpose of this blog is to explore primarily democratic structures, it is important to note that these two principles do not exist in isolation. Rather, they exist in lockstep with one another in a form of democratic and reflective 'coupling', where democratic practice allows students to direct their experience reflective practice allows students to evaluate their experience. Implementing democratic principles doesn't necessarily alleviate the challenge of teaching for meaning in PE. Differentiating instruction and activities becomes increasingly difficult as interests broaden, goals narrow, and perhaps class size increase. However, when I speak with teachers about democratic practice, a common assumption emerges; that the choice of activity is the only / most impactful way to offer choice. While that may be a great way to build democratic practice into a PE program, it is not necessarily logistically feasible in many school contexts. Fortunately, that is not the only form of choice that we may offer students. The purpose of this blog is to try and categorize / visualize different ways that students might be offered choice in PE. Many of the diagrams below will start with the concept or learning outcome as the first step in instructional design. This is a product of my own teaching context in the International Baccalaureate curriculum which is concept / inquiry-based. While not all curriculums are structured in this way, a conceptual approach to learning does align itself with effective implementation of democratic practice (in my opinion, at least). For example, Nathan Horne's (@PEnathan) inquiry based unit titled 'What Moves You?' , which focuses on a connection to physical activity (as Nathan describes here) opens the door to a number of exploratory and democratic possibilities. If you're interested in learning more about concept-based teaching as it relates to meaningful PE, Lee Sullivan's book Is Physical Education in Crisis? is a great place to start. Note on Assessment - Assessment plays an important role in a child's education. For the purpose of this blog, assessment is shown primarily in the structures below as Assessment Of Learning or summative assessment occurring at the end of a period of learning. The exclusion of formative, assessment FOR or AS learning is not meant to diminish their importance, as both play a key role in determining the types of choices that may matter most to students. The exclusion of the role of formative assessment in the diagrams is only meant to avoid muddling the diagrams and focus more explicitly on the types of choices that we may offer students. DEMOCRATIC CONTENTStudents have agency in choosing what they wish to learn or experience. In some contexts, this can be viewed as a choice of module or activity, where the learning outcomes are specific to the choice. Democratic practice occurs early in the learning process, often before an exploration. Example: Intentionally timetabling two classes of the same grade level (or similar) together to allow students to choose from two different activities offered by two different teachers. DEMOCRATIC MEDIUMSStudents have agency in choosing the medium (or activity) through which they will explore the given concept of learning outcome. After an initial sampling of a variety of activities that connect to the concept of learning outcome, students might choose which one they would like to go deeper into. The chosen activity will be the activity through which they will demonstrate their understanding of the concept or achievement of a learning outcome.

Examples:

DEMOCRATIC PROCESSFor very valid reasons, teachers often select an activity through/in which learning will be demonstrated. A democratic approach to process gives learners agency in designing elements of the process / progression within the given medium/activity. The sub-categories listed below are influenced by the paper by Stefanou et al (2004) although specific mention of how they may manifest in a PE setting were not discussed.

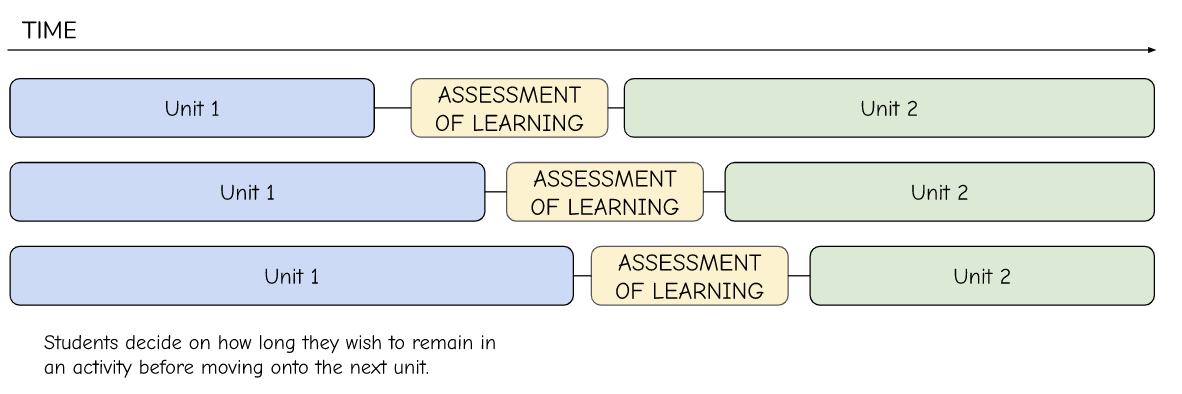

Examples: Applying the MPE Framework to the Grade 5 Spartathlon In this unit, students participate in an adventure triathlon in which they choose the distances they wish to run and whether or not they wish to do so SOLO or with a partner. Learning to Love Running - In this LAMPE Pedagogical Case Study, the teacher allows students to make choices between different forms of running (obstacle, short & fast, long & slow etc.). For more case studies visit the LAMPE website here. Meaningful Experiences on a Bike - In this unit, Andy Vasily (@andyvasily) & co. set the learning outcome as exploring challenge on a bike, through on going reflection / self-assessment students identified goal areas and were empowered to pursue them. What other forms of democratic practice might be utilized?DEMOCRATIC CURRICULUM DESIGN - Every year teachers make decisions about learning is to be included in the scheme of work for that school year. To what extent do students have a voice in that design? To what extent are the activities that are relevant to students prevalent in their PE experience? How do we gather student voice to ensure that they are? DEMOCRATIC DURATION - In most contexts, teaching and learning occur in discrete blocks of time, 8 lessons for this, 5 weeks for that and so on. While the duration of units can be dedicated by a number of factors (e.g. facility schedule, weather, etc.) is there opportunity to structure units in a way with a more flexible start and end time, so students have a voice in when it is they may wish to progress from one unit to the next? DEMOCRATIC LEARNING OUTCOMES - Much of what is written above has been written with the identification of the desired learning outcome or concept as the primary step in instructional design. However, we know that there are a variety of learning outcomes that can be addressed through a single activity. To what extent is it possible in your curriculum for students to determine the learning they wish to demonstrate in the given activity. In this example, the teacher might select football as the chosen activity but provides students choice on whether they wish to focus on developing character, strategic or skill-related outcomes through their participation. DEMOCRATIC PRODUCT - As mentioned in the introduction, the role that assessment plays in the learning process is not fully represented in this blog. A democratic approach to summative assessment would give agency in what they would produce to demonstrate their learning (which may be connected with the above on a democratic approach to learning outcomes). Perhaps in reflective tasks, this could be providing students options over the questions prompts they respond to or allowing a personal response to subject matter. In our departments self-study, we identified that in our movement composition units some students associated performing in front of peers with a negative PE experience (while others, whom likely more confident, found it positive). Is a live class performance, the only product that students can create to demonstrate learning in movement composition? Can multiple forms of choice be offered?In her blog posts (Part 1 & Part 2) Mel Hamada (@mjhamada) & colleagues expertly apply multiple layers of democratic practice in an Individual Pursuits unit. Her department chose to explore the concept of challenge with her students and provided students with a choice of medium (activity) through which challenge could be explored (XC Running, Dance, Gymnastics and Rock Climbing). After students selected their activity, Mel continued to implement democratic practice by orienting her teaching towards student goals with a number of process-related choices. What about 'free choice'?At times, offering free choice, semi or unstructured play opportunities for students it is a great way to engage students in your PE program. At my current school, we would offer free choice days; choosing different equipment and environments to our K-Grade 3 students where the focus was primarily on the inclusion of others in play opportunities. However, assuming students always know what is in their best interests and thus allowing students to only pursue movement opportunities that they already previously enjoy would perhaps result in a fairly limited Physical Education experience (Tinning, 2010, p.45). In addition, when participation becomes too unguided, the environment may become educationally irrelevant as increases in motivation do not necessarily result in increased learning (Patall, Cooper, & Robinson, 2008).

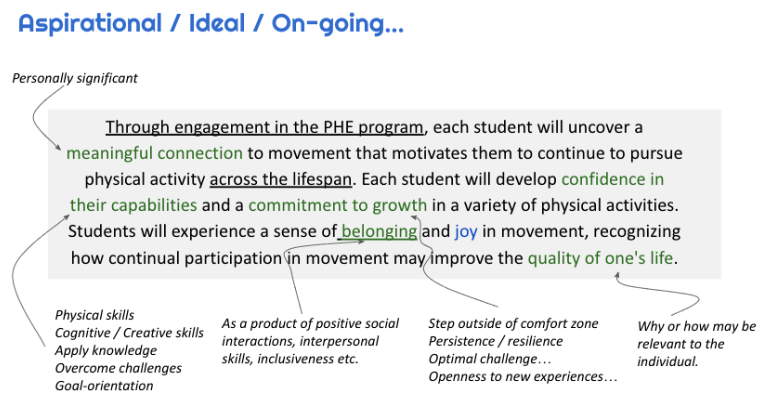

Summary In summary, this has been an attempt to categorize the ways in which we might implement democratic practice in Physical Education. While the visuals make sense for me, I am sure there are other ways to visualize choice and likely my understanding with continue to evolve over time and this post will be a site of continued revision. I feel it is also important to reiterate the importance of the coupling that occurs with reflective practice in this process and that the choices we provide students should be connected to the desired learning outcome and/or conceptual understandings and perhaps not just choice for the sake of choice. What choices do students value the most? To work towards their goals? To choose the activities / mediums they participate in? Is an area of continued interest for myself. References Déirdre Ní Chróinín, Tim Fletcher & Mary O’Sullivan (2018) Pedagogical principles of learning to teach meaningful physical education, Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 23:2, 117-133, DOI: 10.1080/17408989.2017.1342789 Patall, E. A., Cooper H., & Civey-Robinson, J. (2008). The Effects of Choice on Intrinsic Motivation and Related Outcomes : A Meta-Analysis of Research Findings. Psychological Bulletin, (2), 270. Stefanou, C. R., Perencevich, K. C., DiCintio, M., & Turner, J. C. (2004). Supporting Autonomy in the Classroom: Ways Teachers Encourage Decision Making and Ownership. Educational Psychologist, 39(2), 97–110. Tinning, R. (2010). Pedagogy and Human Movement: Theory, Practice, Research. New York, NY: Routledge. In their book Switch: How to Change when Change is Hard, Chip and Dan Heath open the book with the metaphor of the elephant and the rider to explain how individuals are motivated to action. The Rider represents our rational and logical thinking brain, whereas the Elephant represents our emotional side. As you can imagine, oftentimes it doesn’t matter how much the rationale rider attempts to exert control over a situation, ultimately the emotional elephant is the one who is in control. This would explain why despite knowing something is beneficial for us, we lack the motivation to begin. Chip and Dan argue that when companies seek to implement change, they often only attempt to engage the Rider; they present the research, statistics, clear visuals, etc. but fall short due to the lack of emotional investment by those whom they wish to create change with. I was given this book at the end of the 21-22 school year as I prepared to begin as the Learning Leader (HoD) of a new department with new colleagues in the Middle / Senior school. As luck would have it, the gift was about 1 month too late, as I had already failed to introduce the meaningful physical education (MPE) framework to my new team by only accounting for the rationale rider. The purpose of this blog is to share the process of change we’ve undergone as a department since then, as we seek to find common ground between our schools' renewed strategic plan and our individual philosophies in an effort to create more meaningful PE experiences for our students. Contextual Background: At the end of the 21-22 school year, our school released its strategic framework, with the dedicated purpose of creating students who flourish. Many other components of the strategic framework align themself quite closely with student-centeredness, joy and meaning-making. Step 1 - Establishing a Vision Statement What does it mean for students to flourish in Physical Education? If this was to be the centre of our schools educational philosophy, then we should have an agreed upon definition of what that means in a PE setting. I selected two readings:

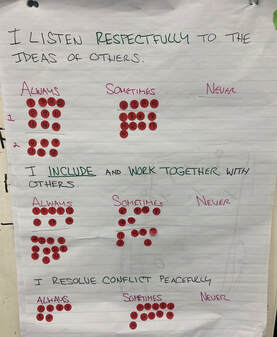

I took all those ideas and attempted to craft them into 3 different vision statements, each attempting to encapsulate the ideas we had in relation to flourishing. At a later meeting, the three options were distributed for feedback from each member of the department who suggested edits / omissions / additions etc. Eventually we landed on some agreed upon components and sought to provide clarification to exactly what certain terms were meant to encapsulate. Step 2 - Establishing a Mission Statement After establishing our vision statement for student flourishing in PE, the mission statement was somewhat self-evident: create the conditions for the vision to be realised by each student (create the conditions for students to flourish in PE). What those conditions are would require some further unpacking. As a group we used a liberating structure called an “Appreciate Interview”, in which each member described a story of a time they were at least fairly certain a student had been successful in achieving our vision for student flourishing. The second part of the thinking routine was to reflect on the conditions that allowed that story to occur (what were the conditions that allowed that student to flourish?) In our discussion, a number of conditions were identified; challenge, connection to community, belonging, new/novel opportunities, peer support, teacher relationship, growth etc. many of which coincide with the features of Meaningful Physical Education as outlined by Fletcher, Beni and Ni Chroinin (2017). Step 3 - Data Collection: Who is Flourishing? While we have developed some agreement on what it means to flourish in PE and began to unearth the conditions necessary for that to occur, there was an important voice missing. To what extent do the students themselves feel they are flourishing in their current physical education environment? What conditions do they see as necessary for positive experiences in PE? The first task was to develop a survey that we thought would accurately represent our vision statement. I used a battery of questions originally developed alongside Alex Beckey, Steph Beni and Declan Hamblin as a starting point. These questions were placed into a Google Form, where department members were able to indicate which questions they thought were relevant to the vision statement, which were irrelevant, suggest new questions etc. After that review, our final questionnaire was built for a last round of feedback, before being converted into a Google Form. The form was completed in class by students from Grade 3 to 12, students were encouraged to only consider their experience this first semester. Step 4 - Data Analysis: What, So What? The data from the survey was collected from 488 students compiled into a near 60 page document, which included different ways of visually representing data, some of which are indicated below. It also included the written responses to the descriptions of positive and negative experiences in PE from the semester. On a PD day, we met as a department and analysed the data using another liberating structure; ‘What, So What, Now What’ or W3. This thinking routine encourages an initial objective analysis of simply what does the data say or suggest? Followed by a determination of why it is important and finally a decision on what action should be taken. At this initial meeting, each individual was assigned 1-2 grade levels that they taught and we focused on primarily the first two questions (or Ws), what and so, what? The guiding questions we used are found below. In addition, to identify the conditions that impact meaningful experiences (or flourishing), we conducted a thematic analysis, where we analyzed students written responses to "describe a positive experience you've had in PE" and "describe a negative experience...", based on the reason WHY it was negative, and not the activity itself, example:

In the above statements, we are not concerned with the activity (bowling / gymnastics), but the condition they identified as being responsible for that experience (positive or negative), in these examples the 3 conditions identified were: fun, social interaction, relevance. What?

So What?

Conclusion The irony of this process, is that it lead us in someways to uncover the exact same things that were already evident in the research by Beni et al (2017) as well as in our appreciate inquiry. Students associate social interaction, challenge, relevance, fun and competence with positive experiences in PHE. So why was taking the time to go through the data more effective than simply reading the research? In many ways, data is emotional - we are passionate about our subject and believe in the value of PE. When confronted with data that suggests despite all your best intentions, students have had a negative experience; that can be hard to digest but also is hard to ignore. On the other hand, reading data that highlights the positive impact you've had on students can be very fulfilling. This data, as it represented our students experiences, was very moving for us a group and could have resulted in hours upon hours of discussion. It is this engagement of the Elephant that has enabled us arrive on common ground and will serve as motivation for future action (now what). References Beni, S., Fletcher, T., Ní Chróinín, D. (2017). Meaningful experiences in physical education and youth sport: A review of the literature. Quest, 69(3), 291-312. For many students, the Spartathlon (a triathlon) is the highlight of their Grade 5 year (10-11 year olds). In this years rendition, students had the opportunity to kayak, bike and run around our school campus. When it comes to traditionally competitive events such as this, I believe there are often conflicting narratives between what teacher's tell students is important, and what we show them is important through our actions (or at least there has been such a conflict in my practice). One on one hand, a teacher may emphasize the importance of the process. Teachers may tell students that the event is an opportunity to challenge themselves and may insist they set goals of a finish time they would like to achieve. They may encourage students on the importance of doing their personal best and not comparing themselves to others. Through these discussions, teacher's aim to help students understand the value of being persistent towards their goals, celebrate the process and define success for themselves. However, when it comes time to conclude the event, what we often see celebrated is not the process, and not individual success (despite advocating for its importance in the lessons leading up to the event). Instead, what we often see celebrated is elite performance, where results from first to last are posted and students who finish in the top 3 of their gender are awarded medals, while those who may have put forth just as much effort (or even more) to achieve their goals, receive limited recognition. For the 10th annual Spartathlon, we wanted to (or were at least willing to) experiment with a way to negotiate these seemingly conflicting narratives and ensure that what we value about Physical Education is evidenced in both ours words and actions. Below I will attempt to articulate how we aimed to apply the Meaningful Physical Education framework to this end. OVERVIEW THE EVENT

PROVOCATION: The provocation for the event was the story of Team Hoyt, a father-son duo who have completed a number of Ironman Triathlons together. Rick (the son), was diagnosed with cerebral palsy at birth and unable to walk on his own, but that didn't stop them. After watching this video as a class we had a number of discussions related to personal definitions of success, approaches to challenges, motivations that are bigger than winning or losing, the limits (or lack there of) of human determination etc. Credit to Andy Vasily for this one way back in 2014 APPEC in Hong Kong. LESSON STRUCTURE: Our unit leading up to the event lasted about 5 weeks (18 lessons) with the lessons divided into 3 broad categories.

DEMOCRATIC PRACTICE In recognizing that our students have a wide range of abilities and experiences we wanted to be able to provide students with the opportunity to create an experience that was going to be meaningful to them. After students had practiced each of the disciplines about ½ way through the unit, we provided students with two primary choices listed below. I believe these represent the choices that individuals often make (formally or informally) when signing up for any sort of race event outside of school. Distance Choice (Challenge) - Students had the option to complete a ‘single’ (400m Kayak, 1km Run, 2km Bike) or a ‘double’ where students would complete two laps / double the distance of each discipline. We were clear with students that there would be no special recognition for completing a double, and encouraged them to think about which format would be a just-right challenge for them. Partnership Choice (Social Interaction) - Students had the option of completing either the double or single event with a partner. As a partnership they were required to start each discipline together and cross the finish line together. We had a great discussion on how having a partner may influence participation in the event. Some students gravitated towards a partnership and recognized the positive influence having a partner can have on motivation. There were a couple pairings who weren’t necessarily friends before the event, that chose to work together for that reason. However, there were also students who preferred not to have the responsibility of encouraging someone else, and preferred to work towards their goals on their own. PERSONAL RELEVANCE (GOAL ORIENTATION) After students had made choices, they set individual goals (or a goal with their partner). We didn’t insist that they needed to be time-based but rather asked students simply what success would look like for them. Some students' goals were related to a single discipline, such as 'kayaking with confidence', while other students wanted to focus on maintaining a consistent pace by not stopping. Some wanted to spend as little time as possible in the transitions, while others did set a time frame (e.g. between 40-60 minutes) of when they would like to finish the event. As a connection to the Team Hoyt provocation, some students dedicated their run to family members. Students had the last couple of weeks leading up to the event to train in the discipline they chose. As teachers we supported students with technical feedback (e.g. gear shifting on hills) and for many, how to pace themselves on the run. On the day of the event, students wore a race bib that had their goal displayed on the bottom. At the concluding ceremony, the students name and their goal were announced to the parents and other students in attendance before they were presented with a medal and then took a picture on the finishers podium.  A student smiles as she sees the finish line, about to complete a 'double' A student smiles as she sees the finish line, about to complete a 'double' STUDENT REFLECTION A few days following the event, students were asked to reflect on their experience. We asked them what emotions they associated with the event, and how they felt about their performance. The large majority of students had a positive association with the experience, words such as ‘pride’ and ‘good’ were often used to describe performance. Some students felt that they didn’t do as good as they could have, but nonetheless had fun along the way. Others expressed they felt very tired but were satisfied that they did their best. When asked how we might improve the Spartathlon next year, only one student asked for the event to return to its competitive ranking format. BUT WHAT ABOUT THE RESULTS… While the priority of both our words and actions was celebrating achievement of individual goals. We acknowledge that some students may be motivated by the rank and order of competition and for them, the emotions of winning and losing may contribute to a meaningful experience. With that in mind, after sharing their feelings of pride and exhaustion, we discussed with them how (if at all) the results of the event would change that? Students then received their certificate which included their times in each discipline (not a ranking), and we informed students of the fastest individual in each discipline. While I don't wish to suggest that the simple gesture of announcing fastest times equates to a meaningful experience for our most competitive students, but it was our way of honoring those students without doing harm to the experience of others. PERSONAL REFLECTION When we decided to move forward with this plan there were certainly skeptics (ourselves included) and a couple parents (of the more talented students) questioned why there were not going to be placings announced, and maybe an eye roll over another ‘everyone gets medal’ event. However, this was out-weighed by the number of parents and students who appreciated the positive impact the new format had. What I observed as students crossed the finish line were exhausted smiles. If you asked me to pinpoint a moment this year where students expressed joy - I would say for many this was it. While there was certainly a nervous energy for some, there was no observable performance anxiety or fear of becoming last. I witnessed students who I hadn’t expected to, really push and challenge themselves. I witnessed students form new friendships through unlikely partnerships, and genuinely support and cheer for one another. No social comparison of “I was faster than you” or “I did a double and you only did a single” was overheard, and for these reasons alone - it was a worthwhile experiment. GRATITUDE I am fortunate to be the 'blogger' of our ES PE team and am incredibly privileged to work with two outstanding educators; Laura Boudens and Michelle Bartoshyk who have been vulnerable, thoughtful and willing to take risks as we attempt to move towards a more meaningful ES PE program. Without them, none of these events would be possible. In addition, school alumni Kiyan Sunderji (shown below), who has completed a number of triathlons and an Ironman came to visit the G5 classes and talk to students about tips and tricks for transitions, positive self-talk during times of self-doubt and nutrition strategies. A student asked Kiyan about his ranking in his events, to which Kiyan responded "I have no idea", describing how it was about doing his personal best which helped drive home the focus of the unit/event. All credit for the planning, organizing and execution of the ROGAINE is a credit to the passion and dedication of Dale Roth and Bruce Hendricks. The below is based on my perceptions and conversations with colleagues during the event. There are many risk management and safety considerations that go into this event, for brevity, many of these have been excluded. The purpose of this blog is not to provide every detail of the event but to examine it through a lens of meaningful physical education.

For those of you who, like me, have never heard of a ‘rogaine’ (excluding the hair growth formula for men), it is an acronym for a Rugged Outdoor Group Activity Involving Navigation and Endurance and the culminating activity of our Grade 10 Outdoor Leadership program. The event focuses on developing leadership skills as students seek to find as many of the 29 markers as they can in 16 hours from the hours of 7pm to 11:00am the next day. As I prepare to shift from Elementary school back to Middle/High school I find myself looking for examples of what meaningfulness might look like with older students. At some point in the early morning, waiting for another student group to check in, it became clear that the ROGAINE may be one of those activities that makes effective use of the meaningful physical education framework; the critical features and as well as democratic and reflective practice which I will attempt to articulate below. OVERVIEW The purpose of this overview is only to provide the reader with a basic understanding of the event for the purpose of understanding its potential for meaningfulness. DAY 1

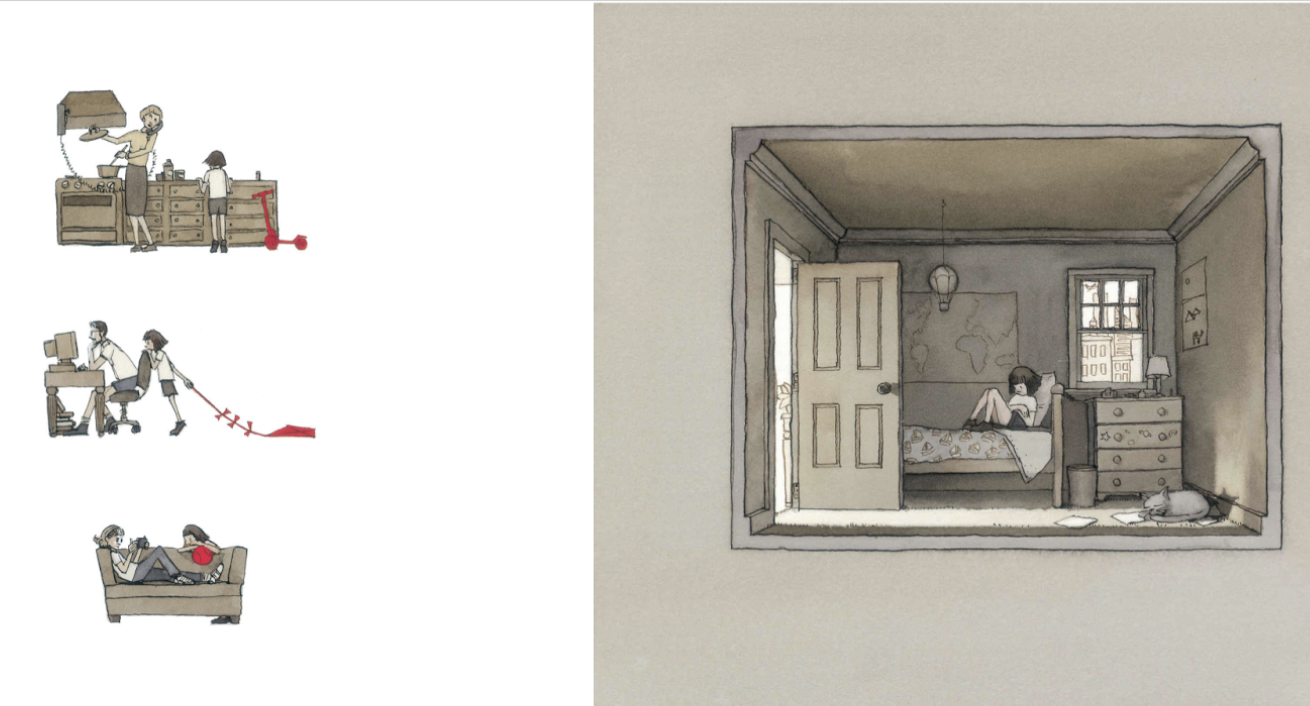

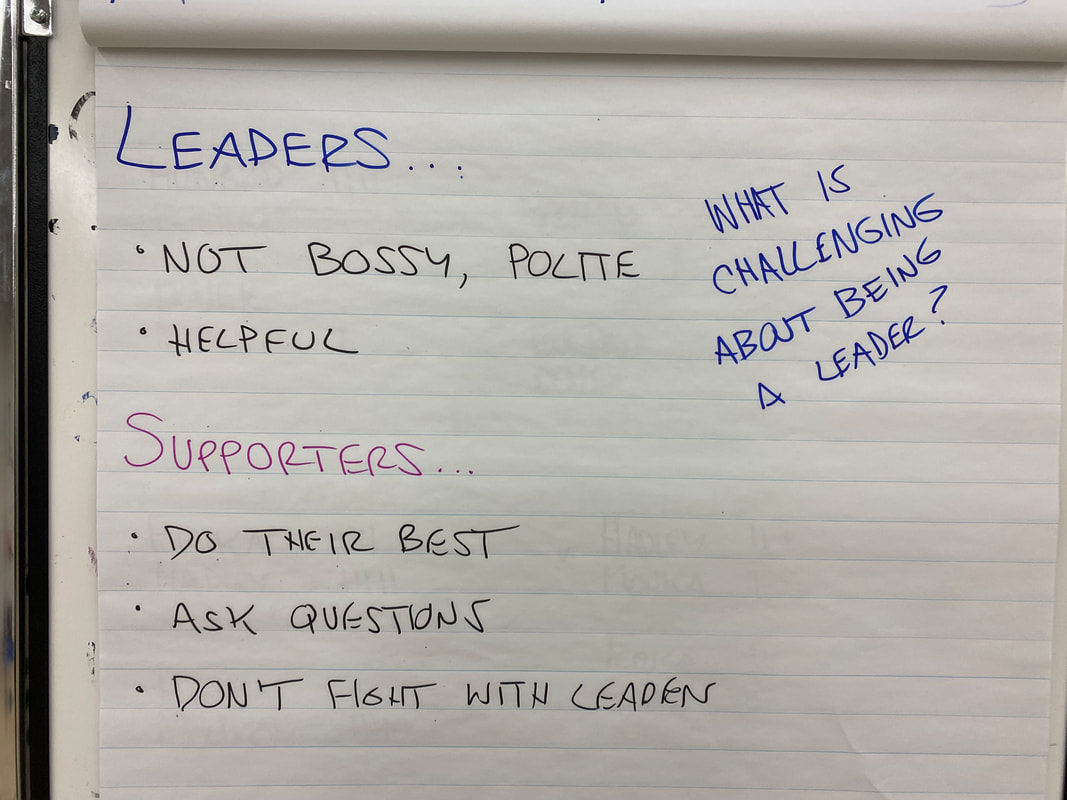

Aspects of the ROGAINE remind me very much of Siedentop’s Sport Education model. After students are formed into teams, they select a team name and develop a team cheer (The ‘Heffers’ ‘ mooooo cheer was my favourite). The students also determine roles, such as ‘lead navigator’, who takes the lead on route finding with the use of map and compass. Other student roles include ‘team mom’, who looks after the rest and nutritional needs of the ground, or the motivator whose job is self-explanatory. A unique feature of this event are the student leaders, who were ‘survivors’ of the ROGAINE from the previous year. These student leaders work with the current years teams by leading them through team-building games, and sharing their insights learned from the previous years successes and failures as they plan their strategy. In my observation, there is a noticeable sense of camaraderie and tradition, as the experience of others is passed down throughout the years. CRITICAL FEATURE: PERSONAL RELEVANCE The emphasis of the ROGAINE is placed upon students building their capacity as leaders. Students are required to set an individual goal for leadership based on the Five Practices of Exemplary Leadership model. Some students' goals were to be more assertive by ‘challenging the process’, while others were to ‘encourage the heart’ and motivate their teammates. What I really loved about the way Dale and Bruce set up this event is that each team member was required to know the individual goals of everyone else in their group. In addition, teams established group norms for collaboration, and a team goal (such as find a certain # of markers, or to stay together as a team). While a winner of the ROGAINE was determined based on the number of markers found (and their respective point value), the reflection of the experience is not based on winning or losing but the degree to which each individual achieved their goal. DEMOCRATIC PRACTICE “Having an opportunity to make decisions that are relevant and meaningful and experience both the positive and negative consequences of those decision seems to be influential in students’ willingness to engage in curriculum” (Ennis, 1999) During the ROGAINE, students are responsible for their own decision making. As a group, students develop their own strategy, they decide which markers are priorities, the order they will be found, and what route is the best option for getting there. In addition to the navigational challenge, rest and sleep are determined by the group needs. Students do not have traditional camping gear and cannot simply set up camp for the night. With the exception of the time when students are able to check in at staff stations (at least once every four hours), students are on their own, and their teacher is not looking over their shoulder to guide or ‘correct’ their decision making. While students do not have a choice over whether they do the ROGAINE or not, they do have significant choice within their learning. REFLECTIVE PRACTICE I think if there is one point I wish to highlight in relation to meaningfulness is that negative experiences are not necessarily detrimental or harmful experiences. In many regards the ROGAINE is a negative emotional experience. Through fatigue, the weather, fear of the dark, sleep deprivation and the challenge of finding orienteering markers at night - students become frustrated as conflict arises between group members. It could be argued that success in the ROGAINE is contingent upon how much suffering you can endure as a team while remaining focused on the task at hand. When I observed students returning to the trailhead (16 hours after it began) many looked utterly defeated. Earlier that night, I sat with a student leader (volunteer) assigned to our staff station. I asked her about her previous ROGAINE experience. She noted that “In the moment it was really hard and frustrating, but now it’s one of my favorite memories”. We know that meaningfulness is uncovered in retrospection, but it is harder to know just how retrospective that reflection needs to be. With that in mind, I believe the most important part of the ROGAINE is not the actual event itself but what happens after it’s concluded. Students do not simply board the bus, and go home to be left with some of those negative emotions. Instead, they stay together at a campground where the first task is to catch up on their sleep. When they wake up that evening, there is a large family style dinner, where students share the stories of their experience with one another. At this point, the previous negative emotions may begin to subside as students develop a greater sense of community through their shared experience. The next day students complete their final reflection where they consider the evidence in support of their individual leadership goal. I believe it is over the course of the 24 hours after the ROGAINE ends, that the real magic happens. Taking the entirety of this event into consideration, it is no surprise why on the night of graduation (2 years after their participation in the ROGAINE) many students state that Outdoor Ed trips such as these, were the highlights of their school careers. Before I get into the unit, I would like to thank Zack Smith (@mrzackpe) for the inspiration to attempt to use storytelling as a provocation for learning in PE. In addition, the wonderful Tracy Tuttosi (@Readervator), for making sense of my babble, in helping me select a book for the unit. The What:

The How

Lesson 1

Lesson 2

Lesson 3

In one particular lesson, Annie rescues a purple bird (my students insist it was a phoenix) from a cage by passing along a bridge. Students use loose(ish) parts to make a series of bridges to retrieve the laminated birds I stuck to the wall. This problem solving task resulted in a various solution involving asymmetrical balance.

Lesson 9

Lesson 10

Lesson 11-12

Lesson 13 - Student Reflection

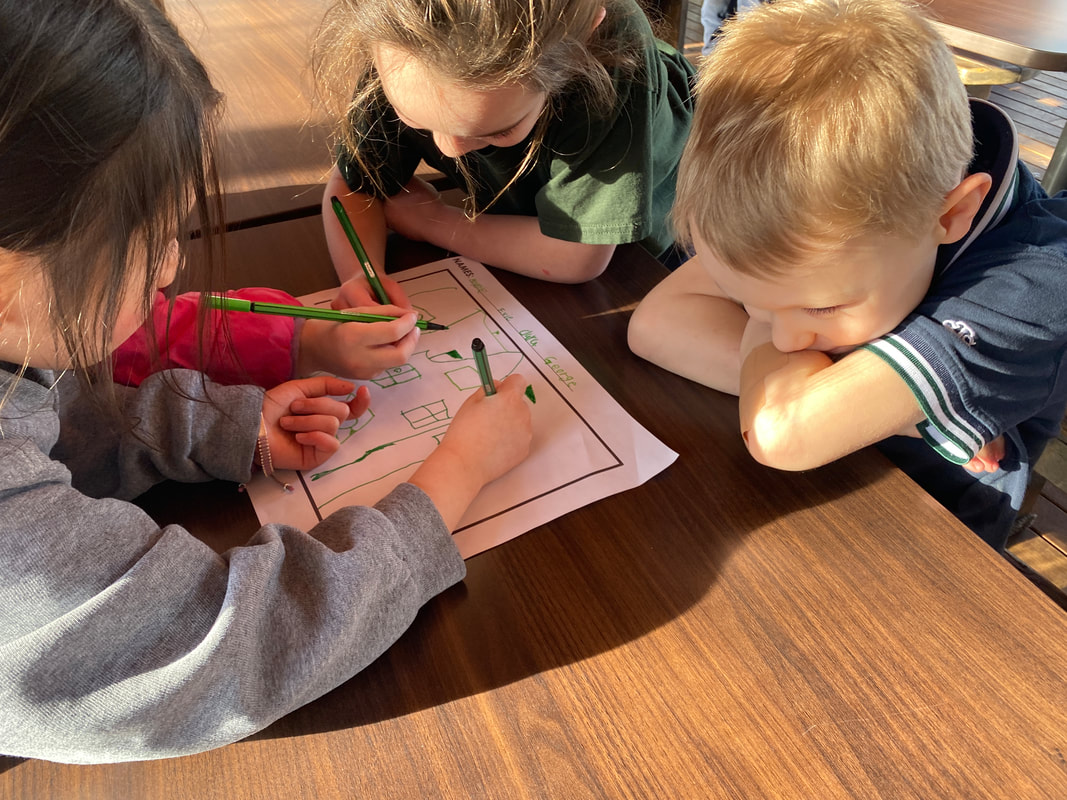

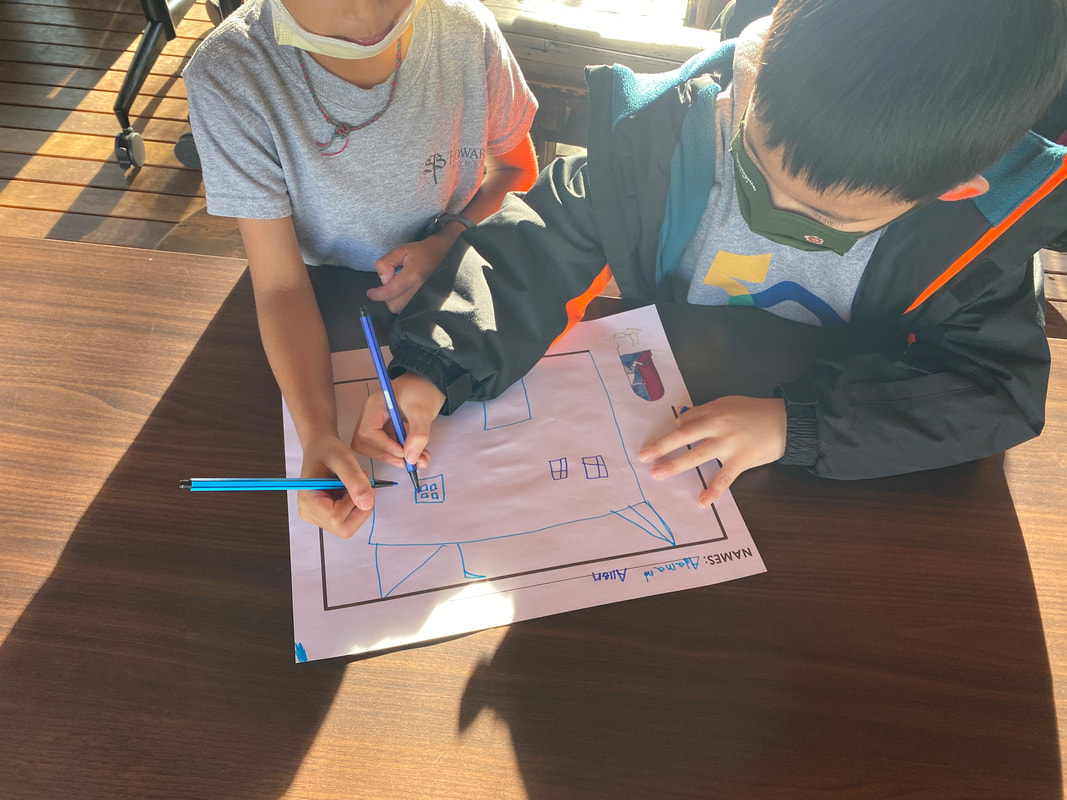

My Personal Reflection In my (biased) opinion, this was the most authentic attempt to guide students to learn to play together that my students have been apart of (I've only been teaching ES for 2 years so take that with a grain of salt). Due to the imaginative nature of the task, it was difficult to tell students exactly what to do, how to do it or roles to take. It was their creation of an idea presented from a picture book that due to resource availability, required group consensus and collaboration to bring to life. To me, the student drawings for the final task look like a bunch of scribbles on a page, but they were none the less able to articulate their vision to one another, where I would have been pretty useless at that task. Additionally, students who I would identify as being somewhat difficult to engage during other units became very eager to contribute to the group project. Early on, students would ask me for help, to lift a mat or to put a tarp roof on, and I remained fairly consistent in suggesting they ask a classmate for help. Over time students began to approach me less and less, and I rarely intervened unless something was becoming unsafe or a conflict escalated.

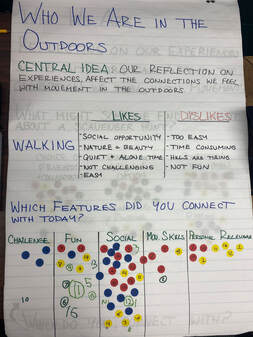

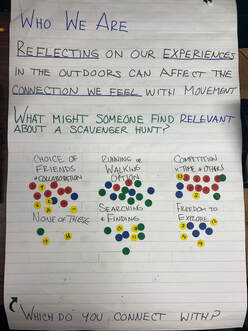

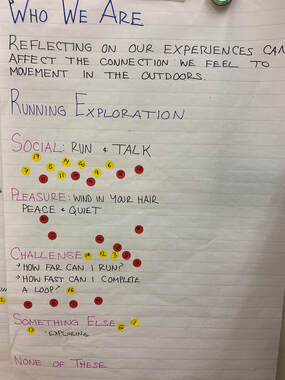

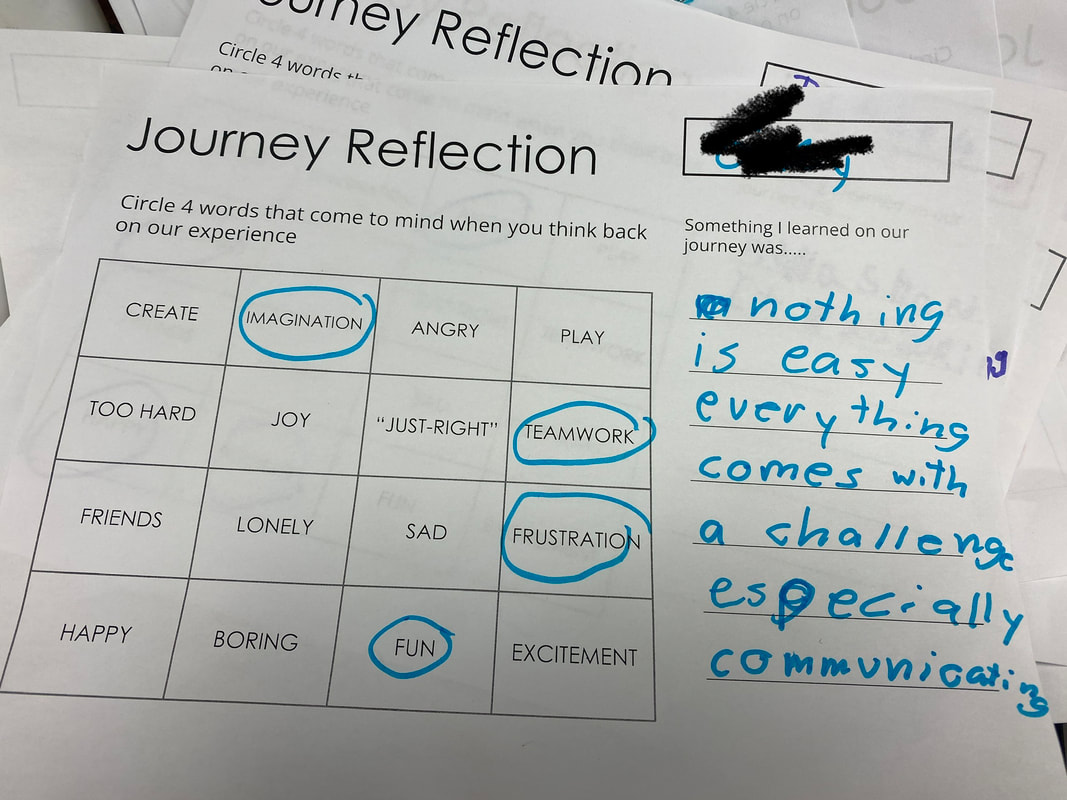

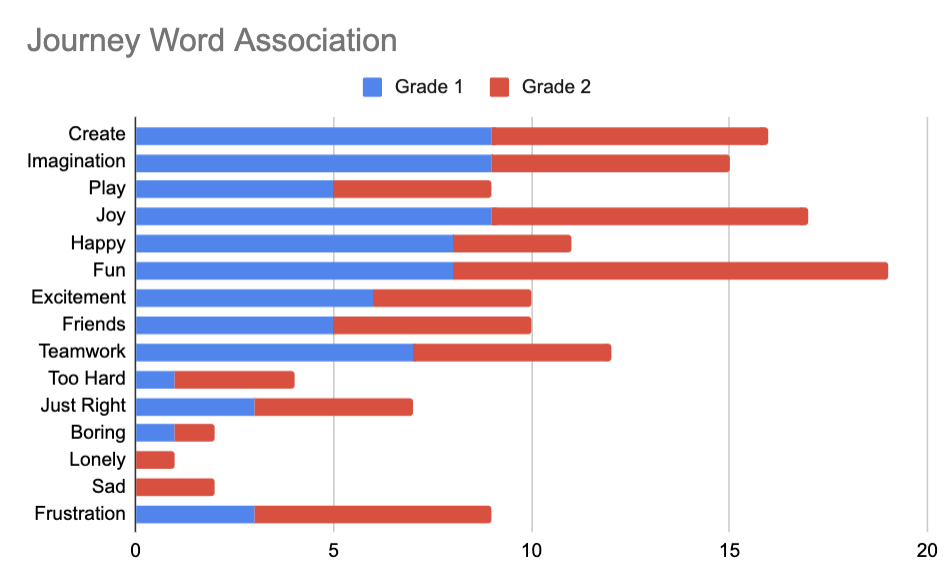

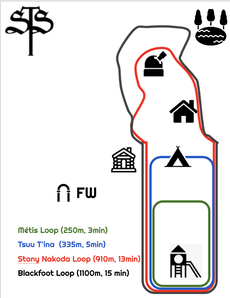

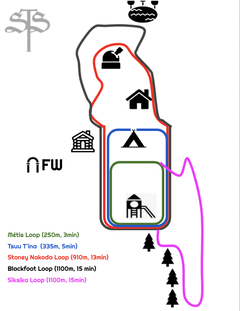

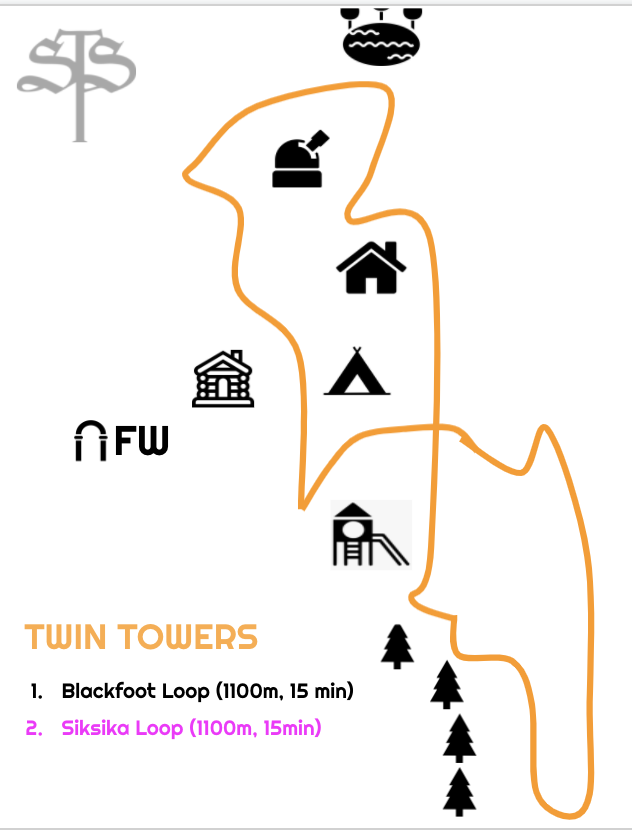

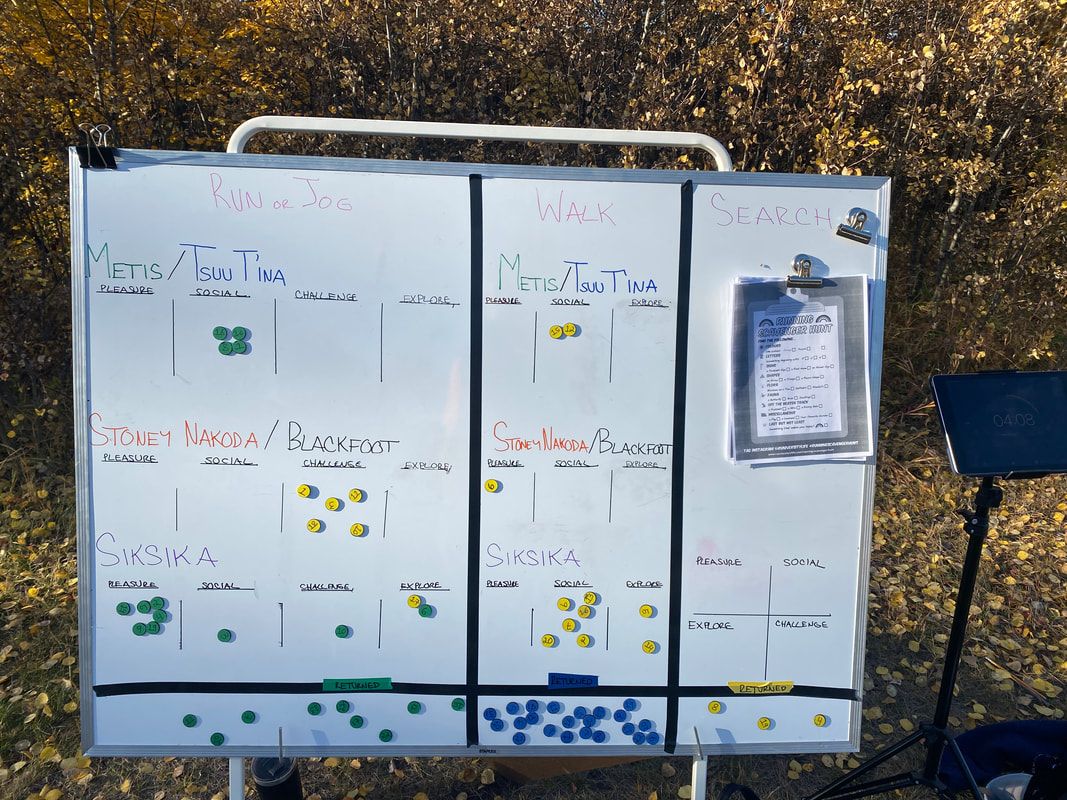

I was pleased with the student responses in their reflection, and not just the positives - but also that 'frustration' was prevalent for a lot of students, and that they were able to separate that from other negative emotions. Frustration is normal, and led to a lot of rich discussions about how it can feel when someone doesn't agree with our ideas, or when we aren't sure exactly what we have been instructed to do by the 'leader'. This led to more discussion about how to cope with frustration. I am interested in learning more about non-linear pedagogy and was really intrigued in parts of the lesson where students moved in response to the provocation of the book. For example, when students build their idea of a bridge to retrieve the bird (or to cross the sea from one fort to another), students end up naturally working on their balancing skills and problem solving in an asymmetrical environment without me explicitly instructing them to do so. However that was only a few of the lessons and even thought I understand the holistic aims of PHE there is still a part of me that wonders if I should focus more on the acquisition of skills through this unit. A few years ago, the first unit of each school year at STS was Cross Country running. The culminating event was the ES Cross Country race, where students would race at set distances (depending on their grade level). Results from 1st to last would be posted on the bulletin board outside the PHE office. For some students, this was meaningful. The thrill of competition and the pride of crossing the finish line before your peers was motivating and garnered excitement for the following years race. For others, the anxiety associated with the pressure to perform, and seeing your name near the bottom of the results list was detrimental. For them running may have become associated with thoughts of dread or embarrassment. Much credit goes to Laura Boudens (@LauraBoudens) and Michelle Bartoshyk for critically examining their own beliefs and practices in re-thinking the annual Cross Country unit/race. Laura writes about her process as part of the Meaningful Physical Education book. I've been fortunate to work with these two and build upon the great work they've been doing. Outlined below is our approach to a unit devoted to students developing an understanding of 'Who We Are'. Through allowing students to make choices of how they engage with our campus trails and understanding the motivations behind those choices. What is not described are some of the more contextual items, such as connections with certain grade- level homeroom classes who were also looking at the trans-disciplinary theme of Who We are (IB-PYP), as well as the annual Terry Fox Run which occurred part way through the unit. Purpose: To continue re-imagining how students engage with our campus trails, and through a process of reflection come to a greater understanding of 'who we are' as participants in PA. Grade/Age: Grade 3-6 (8-12yr olds) Theme: Who We Are Central Idea: Reflecting on our experiences in outdoor physical activity can effect the connections we feel with movement. Time: 4 Weeks (16 x 40min Lessons)  Lesson 1 - Nature Walk In our first lesson, students walked along one of our campus trails. Students had freedom to walk at their own pace, and just needed to check in at certain points. At the end of the lesson, we debriefed on what we might like / dislike about walking. In addition, students used a numbered/coloured sticker (i.e. #3 Red, was always the same G6 student) to identify which feature they connected with on the walk.  Lesson 2 - Orienteering / Scavenger Hunt In our second lesson, students were given a 'Pokemon' scavenger hunt, where Pokemon cards were placed around our campus. Students received a list of hints as to the Pokemon's location, and had the class period to find as many as they could. At the end of the lesson, students reflected on why they/someone might find a scavenger hunt relevant to their interests. Once suggestions were made, students once again used their specific sticker to indicate which they connected with.  Lesson 3 - Trail Running For our third lesson, the task for students was to run on one of our campus trails. While students were encouraged to run, we also made it acceptable to walk when tired. Before beginning, we talked about some reasons why an individual might find running meaningful. At the end of the lesson students once again used their sticker to select the feature they connected most with through running of which social and challenge were the most popular choices. Through offering a choice of "something else" we understood that students were often motivated to explore - to see a new trail, or all the trails within a lesson. The Routes For the next couple weeks (about 10 lessons), students would have the opportunity to engage in a number of 'loops' or routes that went around our campus. Initially, we started with only 3 loops, then every couple lessons we would add an additional route as students became more comfortable navigating the trail system (this was a supervision/safety precaution). The progress of these additions is highlighted below (from left to right) The Choice Board Each day students had the choice of whether the wished to run/jog, walk or do a scavenger hunt/orienteering activity. In addition, we also wanted to encourage students to think about WHY they were making that choice. Students would first select an activity, then a route, and lastly, what they hoped to get out of it. For example, a student would choose to run the Siksika route to challenge themselves. While another group may choose to walk the Tsuut'ina loop to catch up with friends. When students returned near the end of the class they moved their magnet back to "returned" so we knew whether there were students still out on the trails.

Final Reflection At the end of the unit, students completed a "gallery" walk, where the choice board, their early thoughts on walking, running, searching as well as our Meaningful Experience Mural (left). Students completed the attached handout as a rough draft, intended to help them come to some concise statements about who they are as a PA participant in the outdoors. The rough copy was used during the final task, which was to complete a video reflection answering those questions. You can listen to the audio recording of a G5 student's response below. KEY OBSERVATIONS / TAKEAWAYS

|

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

November 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed